#91 Leadership in Emergency Management Now and in the Future – Interview with Eric McNulty

Author Eric McNulty joins us for the beginning of Season 3

This Podcast has moved to the readiness lab.

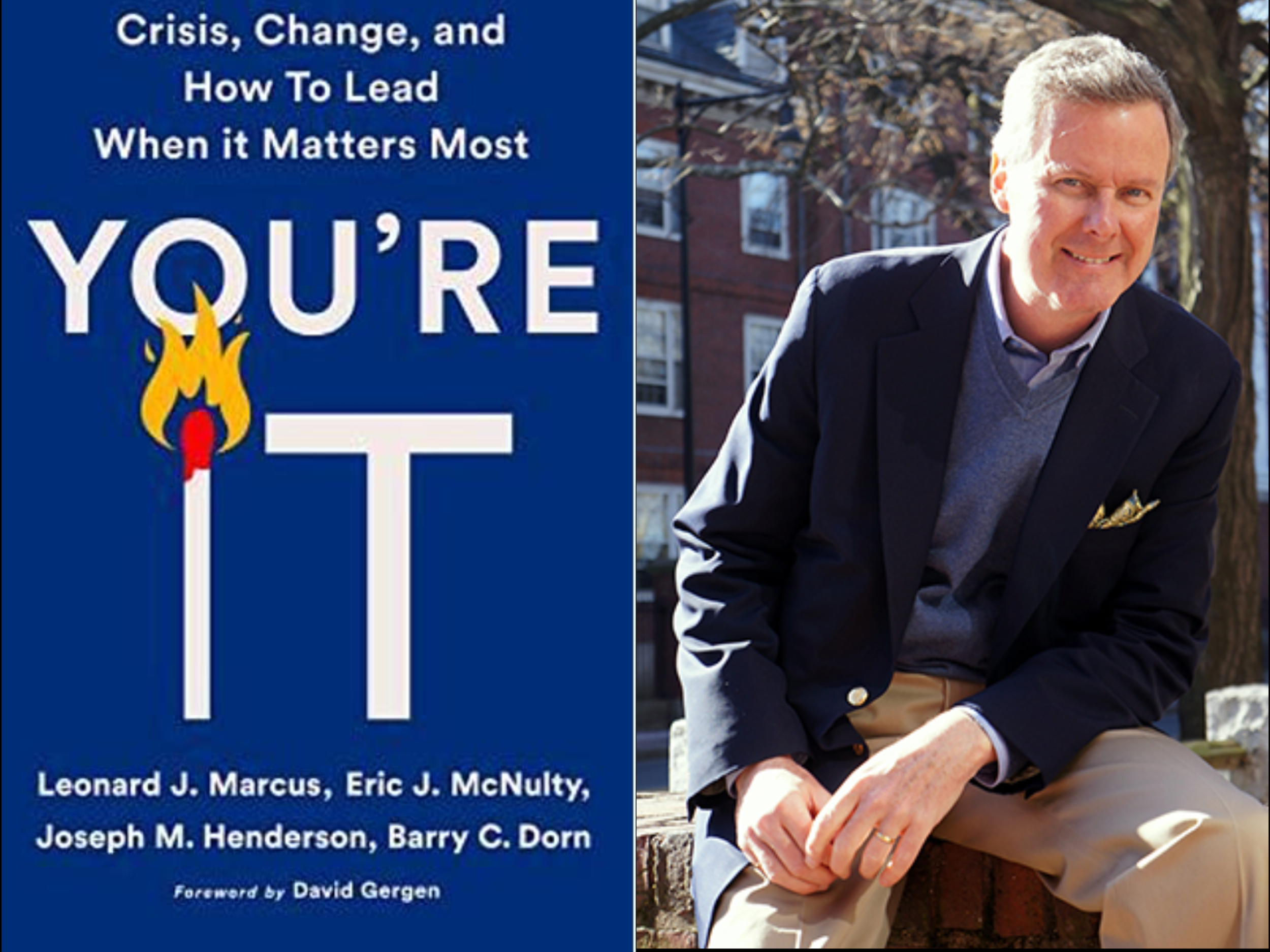

Disaster Tough kicks off Season 3 with an entertaining interview featuring author, speaker, and educator, Eric McNulty.

Eric is a Harvard professor who has been the Associate Director of the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative (NPLI) for more than a decade. He is also the co-author of the bestseller, “You’re It: Crisis, Change, and How to Matter When it Matters Most”.

In this episode, we tap into Eric’s experience in leadership and how it applies to the EM world, together with the importance of readiness, data, and how public and private entities can better work together.

This Podcast has moved to the Readiness Lab.

Host: John Scardena (0s):

You've just entered the Disaster Tough Podcast, the place for emergency managers, first responders and humanitarians who want to get the job done. Stories, lessons and tips are provided by field experts. This show is owned and operated by professional emergency managers at Doberman Emergency Management. We apply disaster tough logic by protecting life, property, and business continuity through planning, mitigation, and training. Check us out at dobermanemg.com or click on the show notes.

Radio comms just got a major breakthrough with the L3 Harris XL extreme 400P, is the newest and toughest radio out there built by their space and tactical teams. The XL extreme series can take a beating, 1700-degree blast of heat, repeated three-meter drops, rain, salt water, you name it, the XL extreme series by L3Harris can take it. Visit L3harris.com to schedule your demo today.

The battle to monitor and contain COVID-19 just got exponentially better for us. We are officially introducing an electronic reusable yes, reusable COVID-19 test through our sponsors. It's called the COVID plus test created by Tiger Tech distributed by FS Global. This is the first FDA authorized rapid non-invasive pre-screener. It's extremely easy to use. Forget those one-time use swabs, this is a disaster tough technology. For more information on the COVID plus test check out our show notes.

Host: John Scardena (1m 42s):

Welcome back to the show everybody, it’s your host John Scardena. I am so excited for this episode. It also kicks off season three for us, we are really excited about that big news for our Disaster Tough Podcast. But this week we have Eric McNulty on here, and you can probably tell on the screen there, that he's the author of You’re It. we're a big fan of that book. In fact, our sister show EM Speaks, the webinar, has had it on there. He was talking about You’re It and those concepts behind that book, he's also been on Todd Devo’s show, a big fan of his with EM weekly. Again, another sister show of our Readiness Lab network. Eric McNaulty comes for the national preparedness leadership initiative out of Harvard. He has tons of experience. He's definitely a thought leader. He and I caught up in New York just a few weeks ago. Eric, welcome to the show.

Guest: Eric McNulty (1m 52s):

Thank you so much for having me here. I'm really excited to be part of the conversation.

Host: John Scardena (1m 56s):

Yeah. So as I mentioned, obviously in your introduction, you are one of those people who are looking at innovating the field of emergency management by looking at the different conceptual aspects, and the functional aspects of our field. We had a fun conversation sitting there getting ready to hear Pete Gaynor and Craig Fugate to be interviewed by Todd in New York. We had this fun conversation where we were starting to name ways that we could innovate our field, especially at the FEMA level, what is FEMA doing and FEMA's role in emergency management. But before we get into that, because again I'm a fan of your book, I think it's a really good thing for industry. Can you just give us a quick little plug for those listeners who might be interested in reading it?

Guest: Eric McNulty (1m 48s):

Always happy to give a plug for the book. Thank you for doing that. What we've done in You’re It, is capture about 15 years of stories and studies of leaders in the field doing disaster preparedness to response. So what we at the NPLI do is we deploy, try and be with people during events or thereafter to see what are the tough decisions, what are they wrestling with? What are the really good calls that they make? Try to capture that and distill it and put it into not just stories, but practical tools and skill sets that people could apply in the field to get better. So we really want this to be a practical book and it's been a really great reception in the field, I think for that reason, because we're not trying to lecture down, we're trying to capture and spread out the good practice.

Host: John Scardena (2m 28s):

Yeah, that's an interesting way to say it. We're not trying to lecture down. Sometimes it's difficult as someone who appreciates data and analytics. I worked for a substantial tech firm after leaving the national team where I led business intelligence for a year and a half. I'm a huge fan of machine learning and AI and all those things. What I find in particular is that our field of emergency management doesn't attack that as much they could, like trying to figure out, I don't know where the tornado is going to land next. Our basic understanding of that is… I got to pump the brakes here for a second, where we were a hundred years ago versus now is phenomenal and definitely weather data in terms of all the aspects of emergency management is far and beyond what anybody else is using for analytics for sure and understanding the physics of what's happening. But in terms of the decision making process, what I find is too many people are still using and I'm going to follow my gut here. I'm sure this is a tiring topic for people who've listened to the show because I've talked about this so much. But as someone who's actually studied this, in terms of a leadership perspective and your studies of leadership, are they doing that? I'm going to follow my gut versus data and what are some improvements we can make between those two sides of the house in terms of the decision making process?

Guest: Eric McNulty (3m 59s):

I think their are a couple of important things there, and one is, I think we are not too many years away from data assisted decision making for leaders being the norm and you're going to have to understand it. It's going to better inform you and all your gut is, it's important to us to understand your gut to all that your gut is actually really good. If you've seen the situation many times before, it's basically accumulated a lot of data, processed it into patterns and it helps you react quickly. You know, the greatest percentage, the greatest number of neural transmitters in your brain, the second greatest number is in your gut. They're connected by the longest nerve in your body up and down your spinal column and they're constantly constant communication.

So if you're in a situation you've seen a lot before that gut killing can be a good guidance. I always say, Ben, go to the data and see what it tells you. But if you're in a novel situation, you want to depend on less than your gut, because you're probably not fully recognizing what's happening. You want to look at that data. I think the tools are coming together and another guest you should have on your show is my colleague, Brian specifically looked at this really deeply in terms of AI and machine learning and how it's going to apply to leader decisions going forward. But I think we're at the point where we have the computing power, we have the data sets. We now just have to have the open minds among the leaders to realize this is, this is a compliment to what they do in an ill health and enhance their effectiveness. It's not a threat.

Host: John Scardena (6m 43s):

Oh man, you, you highlight so many areas. First of all, what a great pitch for following your gut and applying it to data. That's a great pitch. I will say that, you know, you brought up the novel, a catastrophic disasters, especially a type one. Now not a block swamp per se, but a type one event where a lot of what we're doing is trying to go by the fly. I think you're right. You don't have enough data for your gut to be a hundred percent accurate. In fact, your gut, usually isn't a hundred percent accurate, but emergency management rarely is you have to be able to make a decision quickly. That's right, it’s been a fun thing.

In terms of the tech world of data-driven versus data informed, and I really think that's just a good way to help you understand really what it's supposed to do, but it's a branding thing, right? We really want to get to is whatever the best cases, the best case being life sustaining, life supporting missions in the fastest and most efficient way possible, and a decision-making process and having the right information with the amount of time you have. That's the other problem that we have is time. There’s a really interesting call out in a way to look at that so way to way to kick it off the right way, for sure.

Guest: Eric McNulty (8m 10s):

I give you a quick example of a good view outside emergency management, which I think is useful here is in healthcare. Some of the larger healthcare systems now have default protocols for certain common diseases like certain cancers. So rather than a doctor drawing upon his or her, you know, hundreds of cases, they are looking at tens of thousands of cases across the system and saying, this is the default that you can go, you can do something other than the default, but then you have to explain why, but it gives you really quickly having looked at tens of thousands of cases. Here's what looks to be the most efficacious treatment plan for this particular cancer and it gives you a grid. So you can draw upon that larger knowledge. It doesn't take away your freedom to make a different decision, but it makes you think about to why. Why I going against the data and it helps you. I think you really can. It really helps inform the decision rather than dictate it.

Host: John Scardena (9m 3s):

Well there’s a very popular phrase in emergency management that says every disaster is different. That's like me thinking, well, every cancer must be different or every, you know, but I can name 36 manmade, a natural disasters that are going to act the same, right. If I get in there and I see a hurricane, okay, I'm going to see a wind event, I'm going to see a flooding event, I'm going to see a surge event and I can start making predictions and, or, you know we do say every disaster is different, but we stage resources and where we state resources and we put up shelters and how that supply chain is staged. All those factors start to go into play. Same thing with wildfires. We know it's going to be proceeded by mudslides when the rainy season comes. So there is predictability in that.

Guest: Eric McNulty (9m 57s):That's right.

Again, we won't go into too far in the weeds of data, but I believe there's enough data out there for us to start saying, okay, maybe not every disaster is different. Maybe there's a lot of the same and we need to start saying that. So we understand truly routine versus crisis mode, which is a, another reference to another book that's out there and understanding when are we truly in crisis mode? IE is that true novelty? Or are we in crisis mode because we just haven't done the right prep work to make sure that we're being as efficient as possible. So there's some call-outs there for sure.

Guest: Eric McNulty (10m 39s):

In fact, I just completed a research study, went public today, actually interviewed at nine global companies around their response to COVID. One of the places they've at least a couple of them tripped up most because they thought coronavirus is novel. They sort of throw out all the existing protocols and thought we had to start from scratch and it turned out, no, it's just like, yeah. Of the 10 things you had to worry about, four of them may have been in truly new and you have to improvise there. But six of them actually were basic emergency management, best practice. Here's what we ought to be doing and so I think we got to be looking at a continuum of events here, and either or will get us to a much healthier place.

Host: John Scardena (11m 14s):

Well, you're, getting to another, and I have all these passions. One of the passions to me is that public health is great for long-term trends, not great for response. You should be looking at your emergency manager because that's the person who can do response. Public health is one of the pillars that the emergency manager should talk to. The reason being in 2014, I was working at the National Cancer Institute where we were housing, the Ebola patients, building 50. My job was to make sure that there was no patient spread in building 50. Was I a doctor? Absolutely not, but I could work with doctors, I can understand PPE, I can understand the protocols and I can make sure that it was contained. Because of that, when I went over to another federal agency, I got put on the task force to understand what we should do for a pandemic response to reduce spread and we focused a lot of messaging. We focused a lot on this stuff. When the pandemic hit, I was contacting some of my friends in DC and saying, I know we have a plan here. Where's the plan? By the middle of March, I sent him a communication out to some of those former members, “hey, we're now looking at a multi-year thing if we don't get this under control.” They all agreed.

You know, lo and behold, we're at a multi-year issue because the messaging has been really bad. I mean, that's not novel. You know, the work from home thing is a scene. It has seemingly been a novelty concept for people, but they have been doing work from home before. So the one really interesting thing about COVID is the case studies that will be able to come from it. If you said in 2014 hey, we want to put every child at home for a year to do school at home and see what the impacts of doing that would be. People would just like laugh at you out the door. So that the current of a case study, we can see the impacts of a cultural shifts, societal shifts.

Host: John Scardena (13m 22s):

That’s really interesting as well. So the fact that you're talking to healthcare and the fact that you're looking at corporations and how they're doing COVID and doing research on that, I'm sure that this will be a wealth of learning, that the learning growth should go way up from this event.

Guest: Eric McNulty (13m 41s):

Let's hope so.

Host: John Scardena (13m 42s):

Yeah.

Guest: Eric McNulty (13m 48s):

Lessons learned versus lessons applied in a whole different thing, you know?

Host: John Scardena (13m 50s):

Yeah, sometimes we like to say, you have to go for the lowest common denominator. I don't think we do that. I think we get pigeonholed and thinking, oh, my way is right and if they don't like it, they're dumb. That's a stupid way to look at it as in terms of just being totally honest. You want people on your side and creating trenches of how people feel about things is never effective. You know, a good example of that is we've had gangs, rival gang stay in the same shelter. How do people who traditionally don't get along, stay in the same shelter? Well, yeah, come up with compromises and you work with leaders and you say, hey, there's something bigger here that's happening. I didn't really see that in a pandemic. So that's a whole other thing.

But in terms of New York, getting to like kind of bulk of our conversation, we were talking about several things, changes that we would like to see in the field of emergency management. It was kind of fun because as Craig and Pete were on the stage with Todd, you were kind of looking at each other for everybody. And we're like, oh, call that, call that. So let me just ask you for the sake of our audience. If you were going to look at the field of emergency management, what changes would you like to see in our field? More importantly, how do we actually implement some of those changes? What are the solutions that you think we need?

Guest: Eric McNulty (15m 22s):

Well, I think I'm going to get a little bit wonky on you here for, just for a moment, because it's one of the findings that came out of this coronavirus study as well, is that I think we need to engage in what's known as double loop learning. So single loop learning is you try something, you get, you see what happens and you may adjust your strategy or tactics. The double loop learning is when you can go back, when you get that feedback and you actually question your underlying assumptions. I think that's where emergency management needs to go with questioning the underlying assumptions from when FEMA was founded from when, you know, as the field has grown, what's still true and what has changed. So, for example, I think one of the things we've seen in COVID is that our traditional belief in a bottom up system, which works really well for a local or regional disaster doesn't work well at all for a national or continent wide, or in this case, a global incident, because I can't tell you how many stories I've heard of people having to deal with all the different guidance from different states and localities. For organizations operating across the country, and it gets worse and you get international that doesn't, but that bottom up piece doesn't work.

So I think we have to be thinking about one thing I want to look, we want to look at is when can you actually flip a switch and say, this is coming down more top down and we're going to have to have some coordination across the country, across jurisdictions in order to be able to address it effectively. I think we ought to be looking at some of the obvious things that we're looking to do and say, how do we get top talent to really want to choose this as a field or the options you have when you were coming into school? I know there's already a high school, I believe in New York, it's teaching emergency management where you can concentrate on that, but how do we actually attract top talent? Not that we haven't got a lot of talented people in this field, but many of the most talented I've met sort of found their way accidentally.

Guest: Eric McNulty (17m 16s):

Like I never thought of emergency management, but then I had this opportunity, or I met somebody who told me, I drifted into it. Even Pete Gainer, you know, he was career in the Marine Corps and he came out and he said, what do I do? Where do my skills go? He wound up working first in Providence and Rhode Island and FEMA. So I think if it just the data conversation earlier, we think rethinking how we train people to be leaders, to really understand decision-making. It is a science behind decision making to understand how to use data. It's going to be much more complex to operating in this field. When you looked at what we're going to have in terms of impacts of climate, are we going to age the population, which brings up all kinds of new vulnerabilities.

So being able to navigate that is going to be a really tricky thing for folks in the field. I think we need to be…I would be making changes to make the education, bring them up several levels of sophistication and some of these key areas of being able to think forward, make decisions and not just do the basics of emergency management. The basics don't go away, they're still important. But I think if you're going to lead in this field, you're going to have to be up there with the top folks who are working in the corporate world or in senior roles in government. That's some of the places I'd make some changes.

Host: John Scardena (18m 35s):

Yeah. I think those are phenomenal call-outs in terms of the sophistication. That's kind of what we were talking a little bit earlier in that sophistication process of doing that, you know, processes. We have Rodney Mossik on ears, basically the godfather, and yes, truly the godfather of emergency planning, modern day emergency planning because he's retired, but he's still influencing everybody in the field and he's very active in that. He says that process is more important than outcome. As one of my mentors and, and working with him directly on the national team, my change in that is just like slightly different it's process is just as important as outcome. You still have to have the outcome, but emergency managers can understand process, and I'm not talking about paper pushers or what firefighters think emergency managers do. I'm talking about us as a field in our own culture as coordinators working in that process. One thing that's, I think is really fascinating is that Brock Long on my show, Pete gainer on my show, Craig Fugate on my show, and then up on stage Craig and Pete saying the same thing is FEMA is largely a funding organization. The problem with a largely funding organization perspective versus emergency services, and more importantly, emergency response, this small areas of FEMA that focus on, on the National IMATS or kind of the regional IMATS too, but really the national IMAT and USR is that they don't really do funding, especially USR. It's not doing funding, but their certificate comes through FEMA. If you're talking about a top-down approach and you're talking about a more focused approach, what FEMA does for the federal government in that coordination of the Stafford Act and the camera and all those things work well in a large-scale disaster. Hospital, emergency managers, organizational campus, whatever they have to figure out, like, how does this make sense for me? It's kind of a hodgepodge of ideas of like, well, I'll never have a 204, but what do I have? They have to kind of make it up as they go. I would like to see standardization in process so that it can not just apply to the federal government, but it can apply to the other side of the house and really call FEMA what it is.

Host: John Scardena (21m 4s):

It's the funding of emergency services. It's not the actual emergency managers themselves. One other question I have for you is if we recognize that, especially if heads of FEMA are recognizing that they are truly most of the organization, doesn't do the emergency management part, the emergency part of emergency management, who else should take that on? Should somebody else take that on if those basics remain, but you're saying that changes should be made. Who else should jump in the game?

Guest: Eric McNulty (21m 42s):

You know, I'm a couple of minds of that one because I, on the one hand, don't want to spread that out so much because you get a lot of divergence in terms of approach and you come up with new problems of how to collaborate and coordinate. There perhaps should be a part of FEMA or maybe FEMA is the, is a funding agency and then there was a response I would like to see them focusing on strengthening state and regional level response capabilities, because I think there'll be, there'll be faster, more nimble. They were better connected to the communities they're going to have to serve. But I also think there needs to be recognition. This is my drum I keep beating since you beat yours on data, is it, I think we are in the early stages of an age that we cannot respond to our way out of when you look at the floods, the wildfires that the recent tornadoes things are going, we simply… the challenges are too big and too complex to simply respond your way out of. So preparedness has got to get its groove back and be, and that's where I think actually FEMA could have a lot of influence in terms of what they fund, what they ensure that the flood insurance program to shape policy in ways that keep us better, you know, preventing things prepared for things. So the, the lights and sirens side of the house is still part of what you do, but you're not relying on them as much. I think we need heroes who are a little bit less than in the dramatic part of the life cycle and more in the getting us ready, because we can't respond our way out of things that are this big, this fast moving in this complex and this constant there's no season for anything anymore, they all just kind of roll into each other.

Host: John Scardena (23m 22s):

Yeah, I agree with that. Talk about the wildfires, the fire crews, the wildland firefighters, or the guys who go out there on those mountains and expect to do that for three months, essentially from late July through October, and really, maybe even August through November, that's kind of the height of traditionally of wildfire season in California. That's gone. So now you have somebody on the side of a mountain year round that exhaustion takes a toll. It takes a toll on the body. It takes a toll on the mind you have turnover, it's unsustainable. What you're saying is truly the way that we're looking at responses is sustainable.

I totally agree. That's why I'm not a fan of resiliency anymore. I think the idea of resiliency being the king of emergency management, or like that that's favorite word for everybody. I don't want to have to bounce back. If I have to keep bouncing back, I'm not going to be able to bounce back. Eventually I've been to the same cities, the same towns for multiple, multiple times of the same event. I'm like, okay, the idea of that disaster tough like mantra or name the company is that we want to make other people, other communities more tough to be able to do with their own response, because at the end of the day, that resource might not be coming. Even if it does come, it will be likely insufficient and I think that's like your call out there is a hundred percent right. My question earlier about who should lead it, have you ever worked with like state guards, like the National Guard?

Guest: Eric McNulty (25m 05s):

Yes.

Host: John Scardena (25m 06s):

Yeah, I understand how the law works, but in terms of a local response, they are essentially the US perspective of the military humanitarian arm. Like if they're doing, they can do crowd control, they help out with floods, they clear homes. They help put up flood barriers, say they do wildfire response. They do a lot of things in emergency emergency services. So if you have a funding organization who is working on a federal perspective and you want to get states and localities more prepared, I would say that they start to segregate and allow states to have people who are highly trained, who are working on this to continue to work on that aspect, answering to the governor. Again, this would not mess with your title 10 or title 32 and whatever that the right number is there. But it would provide a perspective where funding versus response and response is much smaller than the funding. They can separate a little bit because trying to do this isn't really working that great. I don't know my 2 cents.

Guest: Eric McNulty (26m 15s):

Well I think if you want to understand the laws, the governance, the national guard, and then you're one of like six people in the country who do. I've looked into it and it's really complex actually what happens there? Yeah.

Host: John Scardena (26m 25s):

Ah, Virginia. Oh my gosh. Yeah.

Guest: Eric McNulty (26m 29s):

Yeah. But I think that that's one of the challenges, the Guards, they're very good. But they're very much a short-term response for us because they're part-time. So they can get deployed for a couple of weeks, but then all of a sudden, the economic impact of having them, not on their jobs, you can't deploy them for a couple of months. I've seen that in states where they, I know they deployed, it was great short term, but then people got to go home and it's, and you can't have them out there. So I think we've gotta be really looking at what are the risks look like going forward and data that can inform a lot of this. What our likelihood to need, who do we need for short-term medium-term long-term response as we bleed into, as we move into recovery. And yes, I think we should be open to all the different sources of resources and assets. We can deploy against that and figure, how do we best to rate them against the most probable situations we're going to face?

Host: John Scardena (27m 21s):

I think that's a good mic drop moment of the show. Eric, god, talk about knocking it out of the park. So I think you're right. I think we need to be open. I think things are changing. I think the data's going to be showing that it's already been showing that it's changing the frequency of catastrophic hurricanes alone should tell us something that frequency of wildfires alone should be telling us something, the frequency of active shooters. Maybe we should actually look into the real data of why that's happening instead of like the fluff pieces you hear on media and really dive in deep of why that's happening. Thursday paper and somebody's master's program about cross narcissism and the rise of active shooters, but whatever, you know, there's a lot of this stuff that's happening.

Host: John Scardena (28m 9s):

So great all-out don't want to be doomsday preppy, but you're right, we need to be nimble, we need to focus on what's best for the future. We're getting into new phases. You're calling that out as a thought leader. Again, You’re It. This is where my wrap up here is for the show, if you like, what Eric just said, which you should have, that mic drop moment that he just had, and you want to learn more about Eric's perspective on leadership and learn how to be a better leader yourself read You’re It. I'm sure Eric, you and I should continue this conversation. I had to stop yet you're blowing me up too much. So this is good stuff.

Guest: Eric McNulty (28m 49s):

We can always get tenured, always happy to talk with you, John.

Host: John Scardena (28m 51s):

Yeah, absolutely. So again, if you liked this episode which you should have. Here's that shameless plug, you give us a five-star rating and subscribe. If you do that, you'll hear more great content. Maybe Eric will come back on the show. Hint Hint. Since we probably should have him back on the show and we'll see you next week.

#90 Disaster Tough After Action

This episode has been archived. After our own after action, we determined that the content in this episode does not promote best practice, does not represent the facts, and does not help you become disaster tough. Please check out another episode for better information.

#89 Football & Christmas! Interview with Matt Hernandez

Matt is a former player, assistant coach, and serviceman with the United States Army. He now works to help communities improve emergency and social services.

Matt is no stranger to emergency and disaster services. Throughout his career in Military Service, working in hospitals, or now with technologies that improve social services - Matt is an excellent example of a heart full of service during Christmas. He is also familiar with having family members in emergency services, after all his father is Joe Hernandez, USAR subject matter expert and practitioner. Matt talks to us from both sides of the coin, as a son and as a practitioner, providing great advice for us to help others or those that may need an extra helping hand during the holidays.

We talk a lot about football during this episode. Matt is a former player and assistant coach for the US Army football team. He shares insights and examples of how we can deal with crisis mode vs routine mode in disaster.

This Podcast has moved to the Readiness Lab.

Host: John Scardena (0s):

You've just entered the disaster tough podcast, the place for emergency managers, first responders and humanitarians who want to get the job done. Stories, lessons and tips are provided by field experts. This show is owned and operated by professional emergency managers at Doberman Emergency Management. We apply disaster tough logic by protecting life, property, and business continuity through planning, mitigation, and training. Check us out at dobermanemg.com or click on the show notes.

Radio comms just got a major breakthrough with the L3 Harris XL extreme 400P. It is the newest and toughest radio out there built by their space and tactical teams. The XL extreme series can take a beating, 1700 degree blast of heat, repeated three meter drops, rain, salt water, you name it. The XL extreme series by L3 Harris can take it. Visit L3harris.com to schedule your demo today.

The battle to monitor and contain COVID-19 just got exponentially better for us. We are officially introducing an electronic reusable yes, reusable COVID-19 test through our sponsors. It's called the COVID plus test created by tiger tech distributed by FS global. This is the first FDA authorized rapid non-invasive pre screener. It's extremely easy to use. Forget those one-time use swabs. This is a disaster tough technology for more information on the COVID plus test check out our show notes.

Host: John Scardena (1 min 41s):

Welcome back to the show, everybody. It's your host, John Scardena. I am very excited for this episode. As you know, Joe Hernandez has been on the show a few times, I think maybe three or four times at this point, he's one of our great friends of our show. I get to go to his USR training that he does with disaster medical solutions. It's phenomenal, I've talked about it on the show, I've had other people on the show, I've had his friends on the show. Now I have a huge honor to have his son on our show, Matt Hernandez, because just like Joe, he's following in his father's footsteps by doing amazing things. I'm really excited to talk to him, Matt, welcome to the show.

Guest: Matt Hernandez (2m 16s):

Hey John, thanks for having me on really excited to be here with you and your audience.

Host: John Scardena (1 min 41s):

Yeah, thanks. I want to talk about Unite Us here in a little bit. This project you're working on or this commitment you're doing with social services, it's really cool. But because it's the Christmas episode, because we're talking about this stuff and our focus is really to help other people, I really want us to focus on that aspect, making sure that all of our listeners, whether they're military first responders, emergency managers or humanitarians, that they know some people out there get it. But before even that, so now we got a third piece. I'm looking at this picture behind you and so for those who are listening to the episode, this is from, I believe what Matt told me is the 2010 Army vs. Navy game. Matt has a kind of a cool experience working on that side because you actually worked as an assistant coach for the Army. Is that right?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (3m 18s):

Yeah, I was a 2008 West Point grad. I played football there four years when I was at West Point. Then, after I graduated, they have this program where they keep some folks back like athletic intern or grad assistants. So I got to coach an additional year after I was there. So it was a pretty neat experience to see things from the other side of the table, put together game plans and mentor some of the guys I used to play with. Really neat experience.

Host: John Scardena (3m 45s):

Okay. So first of all, I didn't know you played too. What position did you play?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (3m 50s):

I used to play defensive end.

Host: John Scardena (3m 52s):

That's awesome.

Guest: Matt Hernandez (3m 54s):

About forty five pounds ago.

Host: John Scardena (3m 56s):

I was going to say you look like you’ve thinned down a bit. You know, last week we had Dan Scott on here with EM student and he talked about emergency management as being the coach of a disaster. He went into kind of his ideas about that. I explained what I thought of emergency management to be as the analyst up there watching the game from below and trying to figure out how to get the ball down the field. As a guy with an actual coaching experience, with actual logistical experience of helping literally the ball moved down the field, whether it's getting the team there or whatever, can you provide at least some of your experiences as a way for our listeners to start spinning the wheels of how emergency services, how they can apply the game of football to possibly emergency services or even social work, that kind of kind of idea?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (4m 54s):

Sure. I mean, I think a lot of it boils down to preparation, right? So I mean, people see the product on a Saturday or Sunday, if someone's playing a football game, obviously if an emergency is taking place and you’re physically trying to help and assist, you're seeing the product as it is, but the preparation that takes and the repetition and the understanding of you have to be an expert in your craft in order to be an expert in those dire situations, right? When your blood pressure's up, when people are relying on you to do your job, if you don't take the proper steps to prepare and to walk through the motions and understand what your role is and what your team's role is, you're not going to be successful. So I think people see you know, that game time scenario and I'd apply the same thing to the military. If you're not training the way you're going to fight or practicing the way you're gonna play or preparing the way you're gonna end up saving, then you're going to be missing. You're not going to be performing the way that you should be when the time is right.

Host: John Scardena (5m 51s):

Yeah. I think this applies also like I said, training, because I've been a part of so many exercises as part of getting ready for a big disaster. Whether it's a hurricane, wildfire, or literally preparing for a nuke where every single exercise from that same training group always was a lightning bolt exercise. Which basically means there was no preparation whatsoever. Like all of a sudden we're in a category five hurricane, like nobody saw this coming for the last five days? Right. And what I've been finding is that going to you know your dad's USR training, their model is phenomenal. I played sports as well, you know, you're not always in the game, right? Like there's skills that could get taught in a slower environment. Then once you're able to apply the skill, then you get put in the scenario, right? In terms of game time versus preparation time, what do you think the ratio of that is?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (6m 55s):

I think it's… I work with a lady and her dad's actually a coach in the NFL and she says, you know, you practice for six days and you play the game on, you know, on a Sunday, right? With the NFL in mind, you're practicing six times more than you're playing. I think that's at a minimum, it's an iterative process. Like you said, like you got to build up on the little things, you got to do little things, right, in order to put everything together. Everything's about preparation. I think it's also just having a plan too, right. So having, having a strategy about how you want to act in a certain scenario. Or how you want things to unfold, there's always variables you can't control. But if you plan for certain scenarios, then you're going to set yourself up for success. One of the things that we did in the military and actually applied this for some emergency management prep when I used to work in the hospital environment was you prepare for the worst thing that can happen and you prepare for the most likely thing to happen.

If you can figure out those two scenarios, you can pretty much figure out anything in between. I liked that. So we use that, we use that application. We used to prepare for emergencies when I worked down in Miami and in the hospital environment. That's what we would do. If we just took that concept, what's the worst thing that happens to make sure we have a plan for that. Then what's most common and we'll be good and figure everything out on the fly. If, as long as we prepare and have the right plan,

Host: John Scardena (8m 8s):

There's a book. I forget the name of the book, but this actually might be the name of the book Crisis Mode Versus Routine Mode. The last chapter in that book talks about those who basically, the way that we'd always looked on the national team was everything. Any situation we went into was crisis mode because the people that were there, the resources were overwhelmed, the game plan wasn't working. So we were specifically called in to fix. We had to take crisis mode to routine mode. The problem with that though, is like, sometimes people get the adrenaline rush in the crisis mode so they think they should stay in crisis mode.

My big pitch is that again, with a lot more training, you should be able to get to routine mode as fast as possible. The flip side is, if this is okay, this is not the year for football for either of us because I'm an Ohio state fan. Yeah. That was painful. Well, you know what? I have a theory on that. It's a conspiracy theory, but I have a theory. Anyways, the problem is when people are in routine mode, but they actually should be in crisis mode. If you're preparing for the worst case scenario and also the most likely scenario, then again, you're going to be able to tell the difference between routine and crisis. So great thoughts there. So what was the final score? I don't want to bring this up, Navy versus Army this year? You got, it was a tough year, right?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (9m 48s):

I try to forget that. Right. I think it was 17-14. So we it's funny, we were underdogs against Air Force. We'd be there for us. Then we were favored to play when we played Navy and we lost the Navy. I mean, those games are just always so competitive. Right? You have a long-standing rivalry, which you understand now. I mean, Ohio State owned Michigan for a long time. And now, you know, Michigan had the last laugh. So.

Host: John Scardena (10m 10s):

Well, just say last laugh, don't say laugh. Okay. First of all…Here's the conspiracy theory, Jim Harbaugh, the guy's a moron. The guys like Tara, look at his record at Michigan. He's done so bad against Ohio State, obviously and against everybody else. But the problem is if they fire Jim Harbaugh, Jimmy, whatever his name is, and they replace him with me, with somebody actually better then it would be harder for us. So I think Ohio State was looking at the cards and saying, okay, are we going to win the championship this year? Probably not. So if we lose to Jimmy and they extend his contract, which Michigan basically just did. Right. We're going to beat them for the next five years and everybody wins. So they got one of six with Jimmy.

We beat them 17 to three.17 years we’ve' beaten them. So I don't know, don't say last lap yet. Fair enough. That is the most that's that's talking about. So when I said routine mode versus crisis mode, I was watching that game. I don't know if this is like the football episode, but I was watching that game and I was like, why aren't they changing the game plan? They were acting as if they were going to win. I see this sometimes with teams and also in emergency services and emergency management. I don't know if you've seen this in the military side where they maybe with the politicians, but they act as if they know they're going to win and they won't update their strategy. Is there advice you can give to people in the field where you're like, okay, how do you know when you're in routine versus crisis and how do you create backup plans?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (11m 48s):

Well, I think it almost tells line of cockiness, overconfidence. Like if you're overly cocky, like that’s where people get hurt, right, or mistakes are made. So, in a football game, you may lose a game or you may make a mistake. If you're talking about emergency management board, military, and you make mistakes, like people can die, right. Or people can get significantly hurt. So I think there's a fine line between being confident and understanding, like we put the preparation in, we've done the right things, we know our job, or we're in the right mindset. Versus like, hey, this is easy, we got this. Like, we've done it a hundred times, that we don't need to focus on what we're doing. Then you lose that attention to detail or that focus that's when you can make mistakes and people can get hurt. So I think you need that constant reminder. I mean, we could go back to the football thing, like Bill Belichick's, right. He always expects you to do your very best. The second that you make any kind of small error, they're gonna critique that and they're gonna find a way to make it better because they don't want people to lose that edge. Right. So you can lose that edge, you're not prepared, that's when mistakes can happen. So I think having leadership understand that, and know that, and instilling that every single time that they need to is important.

Host: John Scardena (12m 48s):

So I find that different people have different personality traits, right? If you're talking about critiquing people, how would you go about critiquing somebody in emergency management? Dude, I can't even get, you're a football player. There's a lot of cocky football players out there. How do you critique somebody who has a lot of experience who thinks they know what they're doing, who is kind of bullheaded at the same time… You know? Because your goal obviously is to help them and help the mission, right. How do you find those lines for yourself?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (13m 25s):

I think like you said personalities are different and so you have to know the folks that are on your team. You know, when I was a second Lieutenant, I get thrown into a platoon, I had a 36 year old platoon Sergeant who had been, he'd been a Marine recon before. So he's been special ops in the Marine side. He had multiple deployments with the army before this guy was way more seasoned. I was book-smart, but I had no field experience and so, you know, I think walking in with some humility and understanding that you know what you know, you also know what you don't know and validating their experience and their understanding is important to level set that mutual respect. But also that you can do a couple of ways. One is, if you just, if there's a standard and you need to follow a standard, then you can talk about what that is. I think another way you can apply it too, is you can always ask them, put the onus on them. Like, what would you have done differently in this scenario? Did it go the way that we thought it was going to go? And if we did not, what would you have done differently? You know, with the experience that you have and sometimes asking them what their opinion is not to say, you'll always do what they recommended moving forward, but validating who they are and understand their experience and giving them a chance to speak about what they could do differently or what we could've done differently sometimes gives them skin in the game and it gives them a reason to want to help the team better. Right? Or just a different approach. Sometimes you can take with those more seasoned folks that have, you know, lots more experience.

Host: John Scardena (14m 40s):

Yeah. That's a mic drop moment. I mean, that's exactly what I would think is the right call. Man, I have so many thoughts on this and I keep wanting to go back to football and we are shaking and go back to football because this is actually pretty fun. What I find is that like, even with myself, I've had to catch myself doing this and you get to people with no experience who are just super passionate, really excited, just want to jump in. They're like, you know, bushy tailed, right? Like this Christmas morning, ah, there you go. Then we have a Christmas proper, it's like Christmas morning, right? You're like, oh, this is what I've been wanting to do. Then they get in there and they get a little bit of experience. The cockiness just shoots way up. What I find with true subject matter experts is that they have all that confidence that they just gained and they have all that experience and they have all that excitement, but they're able to turn it on. I really hate to give this reference. I apologize in advance for all the people who hate this guy. But Tom Brady, I can’t even believe I'm saying this, Tom Brady is a true subject matter expert in his craft. I would say maybe 10 years ago, I was like, I hated the guy. Like he just seemed cocky or whatever, but he's so far into it now that it's like, he lets the game speak for itself. He has all that passion still and he has all that drive. That's a good football pun, you know that's the example of getting to, in terms of how you should act once you're actually there. The problem is there's a huge gulf actually between, I got a little bit experienced and a true subject matter expert. I think it's trying to learn how to manage people in that space. Right? Yeah.

Guest: Matt Hernandez (16m 31s):

It's a good point. Yeah. I'm going to be seeing this new series man in the arena, but it's really awesome. It's about like the journey right from when he was the sixth round draft pick out of Michigan and then all the preparation he put in until he got his moment. I also agree with you. I wasn't a fan of his, I'm a south Florida guy, so I'm a Dolphin fan. Wasn't a fan of the Patriots, but I admire excellence and he's a person that has, he's the best that there is because there's preparation and his attention to detail. Like you said, he's an SME.

Host: John Scardena (16m 58s):

Yeah. I liked that. You got a Meyer excellence. There's a lot of people like that. Your dad's like that for me in the USR perspective for sure. We're going to do one more football analogy cause I really liked this. I gave a presentation to NATO. I was there on their keynote back in September for urban warfare planning. Really fun experience talking to military leaders without emergency services experience and or understanding of how emergency management crisis management in Europe, what it can do for them. It was a fun conversation. The way I broke it out was describing a disaster like chess pieces. I would say, this is my side, this is the other side of the disaster. It kind of walks through that as a guy who played football, do you ever go through? And you're like, okay, that position, that would be this and this position would be that. Do you ever do that?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (17m 55s):

I wouldn't say I use that exact reference. I actually did a training one time when I was a captain in the army and we had to do professional development. What I used was attention to detail. The scenario I did was I broke down a couple of different plays that looked the same, same formation, similar down in distance. A couple of them were run plays, a couple of more play action. It was off the same movement. What I was showing was like, hey, there's a difference in where these guys align both in the backfield and on the line of scrimmage and the initial action, like in the first like two seconds of the play what's happening like one second and two seconds in. So you can see what's happening. It just showed the attention to detail, like understanding what your opponent is going to do in this case. We're talking like the enemy, like your opponent's going to do reading your keys, understanding what you should be doing. And attention to detail matters in combat, it matters in sports and it matters in emergency management too. Understanding getting down to that kind of level, like the expert level, that PhD level of understanding exactly what's happening and breaking them down and then having a plan and then practicing. Right? So I'm seeing it happen in front of me on a screen and now I'm going to go out and emulate what I'm seeing on the field. So I know if this guy was aligned differently, now I'm looking like hey, something is keying me to think that they may be doing what I think they're doing based on what I saw. So I see it, then I practice it and then I execute it. There's a sequence where it's iterative. So I wouldn't say the exactly of like moving pieces in this player was this player. But I have used analogies for football all the time in my work.

Host: John Scardena (19m 27s):

Do you know any pilots? Any chance?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (19m 31s):

Yeah.

Anytime I talked to a pilot, every analogy is about flying every single one. That's how I feel about football players too. At any time I talked to a football player, it's like, oh yeah, it's kind of cool though, that you look at operations as plays and, you know, instead of focusing so much on the players themselves or the positions as the plays of like, what is the objective you're trying to do in that specific play, try to get wins. I actually liked that a lot, in theory.

Guest: Matt Hernandez (19m 60s):

The other thing I say too, just like team sport wise, like, you know, there's other sports out there that people and not to speak. Like I played a lot of sports growing up football, I think is the one sport where you have to rely on every single other person on your team, more than anyone else. Right? Like you have a great basketball player, he could take over the game. Great pitcher, he, or she could take over the game. But in football, yeah. You can have an athlete, but like the lines not blocking or they miss an assignment on the back end. You have to do your job. So it applies in emergency management, or it applies in the military. If you don't have somebody doing their role, then you have a potential catastrophe that can happen. It's really important to be accountable to your peers on doing your role and then also making sure that they're doing their role.

Host: John Scardena (20m 39s):

Unless you're Ezekiel Elliot in the Michigan game in 2018, when you basically put the game on. No, that's a good point. So let's switch gears here for a little bit. I brought up Unite Us earlier, it's a company you work for. Just to for everybody's sake, they didn't pay us for this, but you work there and I was looking it up and I think it's pretty cool, especially because it's like hitting the innovative side of emergency management and especially humanitarian aid. Can you walk through just very briefly about the mission of Unite Us and maybe your own personal story of why you're focusing on emergency management and or helping people?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (21m 28s):

Sure. Our mission is pretty simple as to connect health and social care. We understand that everyone understands clinical care is really important, right? So it's elevating social services and the basic needs, the basic social determinants of health are important in people's lives and how that impacts their overall health. When I got out of the service, I wanted to kind of find something that had mission focus. So when I got out of the army in 2013, I started working in healthcare. It, so I got involved in a hospital system, worked in a couple of hospitals and, you know, like doing, like helping clinicians, take care of patients. I spent another couple of years working on the provider side doing the same thing right now. I'm directly helping clinicians, not for a hospital company, but for a provider focused company.

But I always felt like something was missing. They do great work, but I always thought we could be more proactive about helping people. This is all about driving health into the communities and really bringing health to the people in. Getting people connected to social services like housing and food and transportation, that basic things that keep people healthy, all of that impacts health. The research says 80% of your health happens outside of the clinical setting. So that's what that company's really after. When I realized what the mission they were doing, that I could be more proactive about helping folks that I live next to and, in folks I grew up with, it kind of spoke to my heart and just wanted to jump on and, and be a part of that innovative concept because it's a newer concept part. It's not mainstream yet and so it's been fun.

Host: John Scardena (22m 54s):

Yeah. The fact that you're tracking that progress or all those different activities is huge because like so many people have these touch points with individuals that come in who need services. But to be able to actually track that and track the history of that, especially when they don't have a lot to go on, like there's not a lot to go on for data, especially when you meet them, they don't have that history readily available anyways. The idea that's at least to an organization like Unit Us and the fact that you're going out there and trying to help, that progress. I mean, because that's really what we're talking about is progression for the most vulnerable. That's a mission that I can get behind. That's a mission I think is pretty cool. But let's back up for a second. Obviously, your dad's a pretty famous guy in the USR world with all of his experiences, with urban search and rescue and 9/11 and everything else he's done. Haiti, Oklahoma city bombing, all of that side. Is that why you got in what experiences impacted you and essentially, why are you carrying the banner, carrying the torch there if you will?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (24m 8s):

Yeah. I mean, I think I was blessed to have, you know, a hero dad, right? I mean, you said it, he's done a lot of amazing things in his life and you know, I always saw him helping other people, right. So it's hard for first responders, families like Christmas. He's like sometimes he missed Christmases and birthdays and things like that, but he was helping other people. So as a kid, it's hard to understand that. But as a grownup now, as a father myself, like I understand the sacrifices that some of those guys make, you know, to help other people. There's a story like my daughter, for some reason, loves always hearing stories more so than books where I remember being on a vacation, coming home from vacation with my dad driving. We were coming back, I think from Disney or Bush gardens and there was a bad accident on the highway and so a van in front of us flips multiple times, goes off the highway, skids off into the grass, ends up upside down and it's in like, I wanna say swamp. Right? So it's, it's, it ends up sinking quite a bit into the ground. So my dad, the guy that he is right, goes into crisis mode for a minute and then relies on his training. But he was like, I think I was about 13 at the time he slammed on the brakes, pulls the car over and says, Matt let's go. I'm in the car with my mom, my brother and my sister, but on the, you know, the biggest one of the group. I remember like we had just spent time buying new clothes for school.

I had new shoes on and, you know, silly young immature of me was like, what? My shoes are gonna get ruined. He's like, I'll buy you new ones. So we've run off into the end of the couple hundred yards into the embankment and there's cars. This van is upside down and there's two older, an older couple hanging from their seatbelts. So he walks me through and we get them down safely and then rescue comes and, thank God those people were fine. They had cuts and bruises and we're crying and we're afraid. But when I saw him go into mode like that, and, you know, I spent a couple of times riding with him and his crew as a young man. I was in high school when 9/11 happened. I was in 10th grade and I just, you know, he always said like, just look at the people that are going to help. That’s always resonated with me. So I took a different route by going, you know, in the military, but service was always something I saw growing up, something I respected and wanted to be a part of. I mean, I think he absolutely is an inspiration for what I decided to do.

Host: John Scardena (26m 31s):

Yeah, that's a pretty incredible for both him and you and I hope he did replace your shoes.

Guest: Matt Hernandez (26m 37s):

Yeah, I think he did, but, you know, and I tell my daughter that story all the time, she's like, tell me the story about Papa and you helping people because I think she's got that bug too, which I hope she does. That'd be cool if she does, she's four and a half, but I always saw him helping and, and it resonated with me. It's, you know, it's always stuck with me.

Host: John Scardena (26m 55s):

It's pretty incredible for you specifically too. You called it out right with family members who are in emergency services and for those of us who have good deployed to disasters, right. Then like, you're just gone. There were several years in my marriage that I'd get a phone call and two hours later I'd be gone. I wouldn't know I was coming home and I wouldn't come home for months. So like he, there's a taxation that puts on your family because of that. So the fact that you specifically were able to say, okay, there's greater good out here is a big deal, especially because he had to have been gone all the time between local and national stuff. Your military service, 9/11 obviously was an indicator for military service, right?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (27m 47s):

Yeah, absolutely.

Host: John Scardena (27m 48s):

Yeah. It was a major drive for me as well because of some health stuff I can't serve in the military. So I was like, okay, like what can I, what can I do? I kind of found humanitarian aid slash emergency management and talk about impacting an entire generation of a leader essentially through something that was so horrible and horrible at the moment and still horrible now. It's driven people like yourself to do good in the world and now you're working on helping the most vulnerable populations. I think that's kind of a Christmas message in itself, there's hard days and there's hard moments, but good can come and Goodwill come. Right. I think that's kind of the message I subscribed for, I choose to believe in. Do you have a similar mantra for yourself or how do you look at it?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (28m 47s):

Yeah, I've always said they can always get worse. I mean, I don't know if that's the most positive thing in the world. I think there's a silver lining.

Host: John Scardena (28m 55s):

You should be the emergency manager just for that one phrase.

Guest: Matt Hernandez (28m 58s):

Everyone goes through hard times. I don't think anyone, regardless of where you were born or what's in your bank account or what you do, everyone is going to experience hard times. But I think there, there are silver linings in, in situations. I think finding your tribe, I think social isolation kills people, right? So social isolation is a really bad thing. Finding your tribe that can help you process things is important. Right? I think there's a good camaraderie around the first responders, cause they're always together, right? They work together sometimes, you know, if you're on a fire or EMS side, you're together for a long time. Sometimes it's also getting those families to interact with each other so they can understand what that shared burden looks like.

Because you know, if you're not married to a first responder or you're not the child, the first one, or you don't really know what that feels like, why is my dad not there? Why's my mom not there? Why is my spouse not there? I think giving people a chance to fellowship with each other and have that shared, you know, struggle is important because then they can relate to what you're going through. I think he said there's still a silver lining and you can find one in every situation if you look in the right place. I think there's something to be said about gratitude and understanding. Like, I'm glad my dad is one of those people that wanted to go help people and be out there when other people didn't. I think having a tribe around you is important to, you know, help you get through those times when you do have the downs and there's the ups and the downs that comes with it. But you know, I think having folks around you is important.

Host: John Scardena (30m 29s):

Yeah and you bring up a social isolation, how like dangerous that is. One problem when people are in either a personal crisis or a catastrophic disaster is it's hard for them to see beyond the fence. I've shared a story about a hurricane before. So I won't share that one because I've been called out for sharing the same stories. I'm a dad, so that's the problem. But you know, what was it a year ago? We had a major wind event when I lived in California and it took out the power out of our neighborhood for five days, except for 10% of the neighborhood. As a guy who likes to do analytics and GIS. We live in that 10% of the neighborhood that was fine. But we'd go visit some friends and you would think that they were in a war zone. I say that respectively of the guy, who's actually probably been to a war zone, but they think it's so hard. They could walk three blocks over and just come into our house and be fine. I think that the message with social isolation distance is real. If you go far enough, you will get out of the storm. That might take professional help if you're in a personal thing that might take finding a group, that might take checking out a vacation spot, that might take moving, literally moving, but you can get out of a storm. It is possible. Right. I think that's the message that we're both sharing today. What would be your final thoughts to either a family member or a responder who is kind of feeling like they're in that isolation mode themselves or that, that crisis mode themselves?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (32m 18s):

I think I used to tell folks, I still say this to this day, because I still have, I still communicate a lot with the guys I served with. I feel like people that are those helpers, which we're talking about, they have a sense of purpose with what they're doing on their day job. When they're not actively doing that sometimes and if you are alone, those two things when you're not feeling that purpose and you're kind of on your own is when you can get in trouble. Right? I think there's a couple of ways that you can help bridge that gap. You can volunteer, go to church, you can help in a toy drive, help out a food bank. There's a lot of opportunities to get out and give back. You could do something nice for your neighbor. Like something that you can do to spark that feeling of gratification and purpose I think it helped get you out of that dark spot. Being alone in your home by yourself as is, is not a safe place to be if you're in that scenario. Then I think too, it's like if you know folks that are alone or that may be alone, this holiday season, reach out and offer them to come over for lunch or for dinner or, you know, to partake in whatever your family is doing. Extend that hand out there. Don't take no for an answer. If you think there's an opportunity there to help somebody because holidays are tough, right. I mean, COVID might be back again, right? Everyone's got this hysteria going on and it's been a rough couple of two years. I think just, you know, extending that reach to help other people is important. Also trying to find that purpose of helping others, I think also allows you to feel important and I get that satisfying gratification by helping other people.

Host: John Scardena (33m 55s):

I think that's a message that I think we can all get behind on one last Christmas reference for ya, you know, Christmas cookies and Santa being a football guy. Do you know how to make Michigan cookies by any chance?

Guest: Matt Hernandez (34m 12s):

I don't even know what those are.

Host: John Scardena (34m 13s):

Oh yeah. Well the outcome is they're pretty gross, but you just put them in a bowl and beat them for three hours, which I'm very excited about. But yeah. Thank you. Also, if a Michigan fan knocks on your door or you should pay him for the pizza and see him on his way. I got lots of this. Seriously though, now obviously I do with motion really well, great message. Great call-out it is the, the Christmas message or the holiday message to, if you're doing fine to help out somebody else. If you're not doing fine, go find that help. There is help out there, it's real. Hopefully people got a little bit of an uplifting message they should have from this episode alone. Matt, thanks so much for coming on and talking to me today and talking about football. That's awesome.

Guest: Matt Hernandez (35m 5s):

Yeah No problem. Pleasure to be on.

Host: John Scardena (35m 6s):

Everybody if you liked this episode, which you should have, here's the shameless plug that we do every time you have to give us a five-star rating and subscribe. If you are trying to find ways to either give back, we have relationships with lots of different companies and organizations, nonprofits like the salvation army, Patrick Muggins, but on that, but on our show a few times we can help you out, point you in directions. If you have questions, if you are feeling alone, please reach out, tell us on social media. We can try to point you to a group, or if you don't want to tell us on social media, you can send us an email at info@dobermanemg.com and we will connect you with somebody. We don't want anybody to feel alone right now, especially during the time of giving and giving back as Matt has been calling out. So make sure you do that with us and we'll see you next week.

#88 Interview with Dan Scott, Host of the EM Student Podcast

Dan Scott is the host of EM Student - Relaunch happening January 2022!

This Podcast has moved to the Readiness Lab

The EM Student podcast brings interviews of academic and industry leaders to students who are new to the emergency management field, as well as emergency managers with an always-learning mentality by discussing the multifaceted nature of emergency management, including how other fields interact with EM and what skills are helpful to cultivate while navigating a career in the EM field.

Host: John Scardena (0s):

You've just entered the Disaster Tough Podcast, the place for emergency managers, first responders and humanitarians who want to get the job done. Stories, lessons and tips are provided by field experts. This show is owned and operated by professional emergency managers at Doberman Emergency Management. We apply disaster tough logic by protecting life, property, and business continuity through planning, mitigation, and training. Check us out at dobermanemg.com or click on the show notes.

Radio comms just got a major breakthrough with the L3 Harris XL extreme 400P. It’s the newest and toughest radio out there built by their space and tactical teams. The XL extreme series can take a beating, 1700 degree blast of heat, repeated three meter drops, rain, salt water, you name it, the XL extreme series by L3 Harris can take it. Visit L3harris.com to schedule your demo today.

The battle to monitor and contain COVID-19 just got exponentially better for us. We are officially introducing an electronic reusable yes, reusable COVID-19 test through our sponsors. It's called the COVID plus test created by Tiger Tech, distributed by FS global. This is the first FDA authorized rapid non-invasive pre screener. It's extremely easy to use. Forget those one-time use swabs. This is a disaster tough technology, for more information on the COVID plus test check out our show notes.

Host: John Scardena (1m 40s):

Welcome back to the show everybody! Its your host John Scardena, I'm so excited for this episode. As you've heard several times before, we've talked about EM weekly. We're big fan of theirs, obviously, cause they're one of our sister shows on the Readiness Lab and one of the co-hosts of EM weekly is also the host of EM students. His name is Dan Scott, he's a great friend of mine. He's definitely leading the way in emergency management, trying to get people to think conceptually about some of these topics in our field to try to push that needle so it's really fun to have him on the show. Dan, welcome.

Guest: Dan Scott (2m 12s):

Thank you very much. Appreciate it.

Host: John Scardena (2m 15s):

Good. We obviously interact quite a bit between everything that we do and I see on LinkedIn, you're a big fan of trying to inspire other people. You put up these quotes, you put up these comments out there to try to get other people. What motivates you or what's what's driving that for you on your side of the house of why you think you should be doing this?

Guest: Dan Scott (2m 41s):

Oh, well there's a couple things that drive me to do it. One is that ultimately, I need to see this stuff too. I need to be practicing what I'm trying to preach. But ultimately we see in our field of emergency management and this is opinionated in my area having done this for so long, because we don't see enough leadership and we don't see enough people taking action. There's a lot of theory out there. There's a lot of emergency management, which they feel that ultimately they need to be reserved there. A lot of reserved emergency managers out there. I'm trying to bring a little bit different approach to how we do emergency management a lot more forward, not just forward thinking, but a forward acting, being more out front, more vocal in what we do and how we do it.

My goal behind the inspirational quotes is to push people a little bit further, but also to engage them with questions and how do we get better and not just as emergency managers, but as people. Ultimately how we increase what we do and how we are, who we are, and how we approach things will definitely increase in and improve the way we do our jobs and whether it's emergency management or something else. I mean, my goal isn't to necessarily only, only approach emergency managers. That's what I am passionate about myself. That's what I love doing. It's what I do. But it's ultimately just in general, what we do and what we go about doing every day that we do it with passion and we do it because we want to be doing it not because we have to do it. If we do have to do it make the best of them.

Host: John Scardena (4m 21s):

Yeah that’s really good call out. You used these words like leadership, passion, and inspiration and people trying to get people to take the lead. Sometimes when people are passionate, it's hard for them to articulate that passion into leadership skills because they get really excited about it. If they're so excited about there, they almost don't want to step in the realm of leadership because they just want to focus on their little pocket of what they think is really important. But the problem with emergency management and emergency management field is that this our field in itself does touch everybody else. I think the pandemic has really highlighted that. I think it's exhausting for people. Great call-outs there. So in terms of your approach of how you want to do things differently and why you think it should be done, what are some examples that you could provide the field that say, Hey, like maybe you should try doing X, Y, Z, and this will be make you a more effective leader.

Guest: Dan Scott (5m 34s):

Ultimately the level of engagement that we see and not during disaster, there’s the emergency manager that we see during a disaster or during some sort of response. Then there is the emergency manager we see, and one of the ways I equate to, we hear this a lot, the blue sky versus the gray sky, right? Well, there is so much we could be doing in the blue sky that would make the gray sky so much easier. In emergency medicine, we hear this a lot. You should never be introducing yourself on the scene of emergency or in EOC. Well we say that a lot, but we don't necessarily practice it when we shouldn't be out engaging more. I've heard this and it ticks me off to no end. It's one of those things I have a chip on my shoulder about it is that emergency manager is usually in her office type could have a plan doing is working in our office. Emergency management in general is not an office driven job. Although a lot of what we do is in the office. It doesn't mean that we have to be in the office everyday, all day. We should be out engaging our community, engaging in our organization. Just recently, we had a conversation with someone on the podcast and it was about engaging the community. Well, you don't necessarily, necessarily need to look outside of your own organization for engagement. You can be engaging those that are within your own organizations to gain partnership, to gain goals that would be to aid you in what you do to aid them and what they do.

You build partnerships in the organization that you don't necessarily know were there, but we ultimately need to be engaging. That's what my goal is, to drive and inspire the emergency manager, emergency manager professional, however, you classify yourself because it's an arising thing. How do we classify ourselves? However, you classify yourself as the engagement that we see in blue skies and in gray sky. When I walk into a room and you got a gray sky environment, everybody should know who I am, what I'm bringing to the table, how I'm going to help them and that I'm there to help. I'm not there to take over. I'm not there to tell you what to do. I'm there to help you. There's no struggle for power. There's no struggle for who's doing what you walk in, you know, your capabilities, you know, each other, you know you're there to help there's trust in the room in gray sky. You build that in blue sky and blue sky is where we need to be spending more of our time.

Guest: Dan Scott (7m 49s):

There's a lot more of it, but we see the gray sky so often because that's what's sexy, right? That's where all the lights and sirens are. That's where we, when we just had the tornadoes. Right? Then I was just big response. What about all the stuff that led up to that, that we could have been doing to aid ourselves and repair ourselves and mitigate against these types of incidents? I guarantee you that wasn't done in previous and now we're this huge response. But as soon as this response over, what are they going to do going forward until the next huge response. I want more blue sky engagement and that's why I'm doing what I do.

Host: John Scardena (8m 23s):